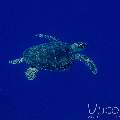

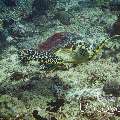

Species images

This species has been seen on the following dives:

- South Male Atoll, 23nd December’23: Bushi Corner

- South Male Atoll, 23nd December’23: Stage

- South Male Atoll, 19th December’23: Kulkulhu Huraa

- South Male Atoll, 27th of August ’22: Stage

- South Male Atoll, 26th August ’22: Kuda Giri

- South Male Atoll, 24th August ’22: Cocoa Corner

- South Male Atoll, 20th August ’22: Kuda Giri

- South Male Atoll, 18th August ’22: Manta Point

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 16th August ’22: Stage

- Tulamben, Bali, 29th October 2019: Bulakan Slope & Reef

- Tulamben, Bali, 28th October 2019: Emerald

- Tulamben, Bali, 28th October 2019: Pyramids

- Tulamben, Bali, 27th October 2019: Drop Off

- Tulamben, Bali, 4th August 2019: Drop Off

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 26th April 2019: Miaru Faru

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 25th April 2019: Gulhi Corner

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 22th April 2019: Veligandu Beyru

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 21st April 2019: Stage

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 19th April 2019: Bushi Corner

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 18th April 2019: Miaru Faru

- South Male Atoll, Maldives, 17th April 2019: Gulhi Corner

- Tulamben, Bali, 3rd January 2019: Liberty Wreck

- Tulamben, Bali, 2nd January 2019: Pyramids

- Tulamben, Bali, 1st January 2019: Bulakan Slope

- Tulamben, Bali, 31st December 2018: Batu Niti Reef

- Tulamben, Bali, 30th December 2018: Drop Off

- South Male Atoll, July 29th, Bodu Giri

- South Male Atoll, July 29th, Lhosfushi

- South Male Atoll, July 25th, Guhli Thila

- South Male Atoll, July 21th, Stage